This is the final post in a three-part series about medical device regulation. See our first post in the Device Disasters series about grandfathered medical devices and our second post on how the FDA's 510k process allows daisy chain approvals.

Device Disasters: The Need for Reporting Transparency

Today we are focusing on the end of the medical device approval timeline - post-market reporting. The FDA's main channel of post-market surveillance is their MedWatch program, which collects data from manufacturers, healthcare professionals, and patients to track the safety and performance of devices on the market. This data, when publically shared, can be used by healthcare professionals and patients to weigh the benefits and risks of devices.

However, the FDA also has an alternative reporting system that has allowed companies to file reports about adverse events that are effectively hidden from the public. This alternative reporting system has led to a lot of problems.

Alternate Summary Reporting

In recent years, alternative reporting systems have gotten a bad reputation mainly because of the agency's Alternate Summary Reporting (ASR) program. The ASR allowed certain manufacturers to submit reports of adverse events or product defects outside of the main MedWatch reporting program. However, unlike reports submitted through MedWatch, data collected through the ASR was not added to the FDA's public database.

When the ASR was originally created, the FDA aimed to improve the review process for certain medical devices like breast implants and blood glucose meters. Rather than submitting an individual report for each adverse event, manufacturers in the program could submit quarterly summaries.

Theoretically, this would simplify the reporting process by cutting down on paperwork and requiring fewer resources from the FDA to supervise devices with common or low-risk problems. The program required companies to limit adverse events summarized in ASR reports to "well-known and well-established risks."

Manufacturers Exploited the Alternate Reporting System

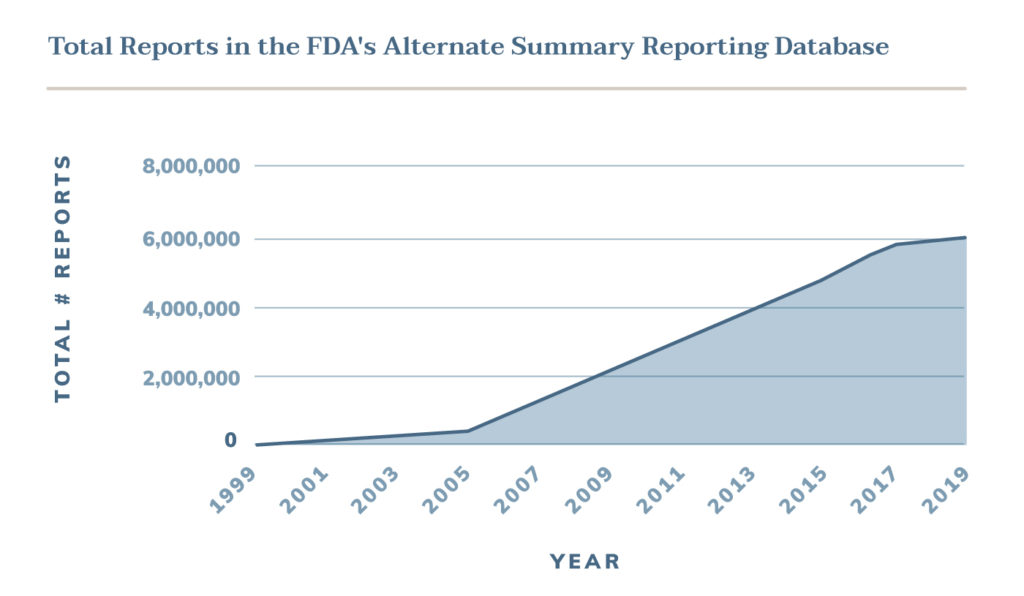

Device manufacturers quickly started to abuse the ASR system by submitting the majority of their device malfunctions through this alternative method - including those that had uncommon or severe risks. The total number of alternate reports skyrocketed from 8,528 in 1999 to 54,604 the next year.

Abuse of the ASR system underrepresented adverse events in the FDA's public database. Doctors and patients who researched medical devices in the MedWatch system received skewed data that misrepresented device safety, possibly leading to ill-informed, life-altering decisions for many patients.

This information wasn't just kept from the public's attention. Even some people within the FDA didn't know about the ASR program or how to access its data. This lack of awareness and communication within the agency dramatically impaired its ability to respond to evolving device risks in a timely fashion.

Device Disaster Reality: Vaginal Mesh

Because of the ASR, the publicly filed data around vaginal or pelvic mesh did not match the true risks of the device. Officials on the FDA's gynecological device advisory panel assessed the safety of pelvic mesh devices based upon only 476 publicly reported pelvic mesh events. However, unbeknownst to the panel, the private ASR database held nearly 12,000 pelvic mesh adverse event reports at the time.

In hindsight, this information could have been incredibly useful to thousands of women considering vaginal mesh over the years. It could have prevented hundreds of thousands of adverse events and more than 100,000 vaginal mesh lawsuits filed by injured women.

A More Transparent FDA

The FDA officially ended the ASR program in May 2019, taking a major step towards more transparent medical device regulations. In June, at the request of Kaiser Health News, the agency took another step forward, releasing 22 years worth of reports collected through the ASR program.

Releasing this data is monumental in the FDA's mission to ensure the safety of the American public. In just two decades, 5.7 million adverse events attributed to medical devices were reported through the ASR program and effectively hidden from the public. In many cases, this information would have completely changed the agency's understanding of device safety.

Several medical devices once thought to be safe have already been further scrutinized because of the reports in this previously hidden database. Similarly, doctors have already changed their prescribing habits for some medical devices. Moving forward, we hope the FDA will maintain their commitment to reporting transparency and prevent manufacturers from keeping device risks out of the public eye.